Kaliko Journal is a free newsletter about natural dyeing, textiles, art practice, and life by Ania Grzeszek. This publication is divided into two sections: ”Plant Dyeing” and “Studio Practice”. You can manage your subscription by clicking “Unsubscribe” at the bottom of the email and opting IN and OUT of the sections that interest you. This is also where you can pledge your financial support for this publication, which would help me continue to sustain it.

Feel free to share parts of this letter wherever and with whomever you’d like, remembering to tag me. If you want to support my work, subscribe to this publication and/or purchase my handmade products. Take care of yourself wherever you are.

Yesterday I went through my stash of naturally dyed fabric scarps and got some examples I’d like to talk about with you. I usually don’t keep any notes of my process, this is not how I work. But I run a test 5 years ago that I actually archived and never shown so maybe today is a good day to evaluate.

In the capitalist culture of “I want the best of the best” we seem to be obsessed with the highest obtainable quality. And the general understanding of the notion of quality in the context of color is longevity. I have a problem with that. I don’t believe that long lasting colors are the right answer to all kinds of projects. If you happened to read my Pocket Guide to Natural Dyeing then you know that I advise to start every project by asking a question: what is it for?

Because the approach would differ depending on if you dye for your own wardrobe, you want to sell products, you dye for fun with kids, you want to make a wall art or a heirloom quilt, you’re going for medicinal cloth, you do it for the love of nature, or you-fill-in-the-blank.

Plant dyes are so wonderful because they:

are a non-toxic alternative to synthetic colors

change and mature overtime

can have healing properties

offer a safe crafting material for kids

you can over-dye them when they fade

foraging helps to get more in touch with nature

natural colors are soothing and they all go well together

But because natural dyes are so complex you can’t have it all.

You can’t have a safe crafting process for kids, for instance, AND make a long lasting colors with them—because you can’t work and not work with metal mordants at the same time (and I would encourage you to skip mordants when dyeing together with kids).

Also, you can’t skip metal mordants AND save water in most cases—because the more lasting the final result the less times you’d have to overdye it, hence you save resources in a long term.

And you certainly can’t have a stable and vibrant yellow AND not use aluminium—because flavonoids (yellow-dyeing compounds) only appear on aluminium mordanted fibers.

There are many processes to choose from, each one with its perks and downsides, and your job is to choose the one that is suitable for your project and your needs.

There’s no question that the color should be long-lasting and stable if you’re selling plant-dyed products and your clients expect that. But if the project you have in mind has a different purpose, I would encourage you to try alternatives. Mordants build a chemical connection between fibers and dyes, which makes the colors last. But you have to work wearing gloves, ventilate your space well to avoid the fumes and make sure not to inhale fine metal powders in the process. It’s not always the answer to your need.

For my own wardrobe, I often worked with soy milk, for example. Soy milk is not a mordant, rather a binder. And by that I mean it doesn’t form a chemical bond with the dyes and fibers, but rather a mechanical one. That means if rubbed or washed vigorously the bond might break. But if the color fades I can always refresh it and I like how uncomplicated it is. Soy milk builds a layer of protein on top of cellulose fibers, and proteins famously take up the dye stronger than cellulose. That’s also why plant colors are stronger on wool and silk than on cotton and linen. Soy milk is a way to work with this property.

Soy milk allows for a wonderful process of painting patterns onto the fabric, too. Below I attached cotton samples dyed with black tea (left) and logwood (right). The pale background was not treated, the darker pattern is where soy milk was painted before dyeing. It really does make a difference, you see.

That being said, these colors are usually less stable than the ones obtained with metal mordants, therefore only suitable for personal use. But it’s a wonderful alternative to metals if you want to treat yourself to some plant magic. So if you’re looking for a safe process to get started, my advice is: go with soy milk, paint, paint over, treat your Tshirt like a whiteboard getting wiped occasionally and ready for a new design again and again. Long-lasting is not always a perk.

Strong tannins like fustic or cutch also allow for skipping mordants. Yes, the color palette is very limited, but I already told you—you can’t have it all. And there’s nothing wrong with earthy tones if you ask me. Tannins, instead of fading, darken when exposed to sunlight, which makes for a wonderful rich patina developing over time. Add black walnut to the mix, a dye that has a slightly different chemical structure and also doesn’t require a mordant, and your earthy color palette… just got even earthier ;)

Tannins can be protected for example with a “sunscreen”. Waxes can build a protective layer that blocks the sun rays, as well as prevents the rubbing off of the dyes. I took advantage of this process for my beloved little wallet I made 4 years ago. Thick cotton canvas was bundle dyed with avocado and then treated with wax. I use this wallet every single day and I’m famously not very careful with things I own. See how the tannins darkened and developed a sort of patina but the color didn’t fade or rub off at all. Plus the wallet is very sturdy and water repellent. The only downside - it cannot be washed. (Notice that I could be describing leather!)

Because this text is becoming rather lengthy, I will only quickly mention two more alternatives. Both require a different process than traditional mordant-dye bond. Plant dyeing is a chemical craft and chemistry can work in many different ways.

So the first process is indigo dyeing, which you would carry out without metal salts, but with reducing agent and in high pH instead. Indigo dissolves only if “reduced” (oxygen is removed) and builds back into pigment when exposed to air (oxygen is introduced). Mordants have no place in this process. If you want to read more, here’s my article about dyeing with woad, and here’s the link to a real expert—Britt’s Insta.

The second process is acid dyeing (not to be confused with synthetic acid dyes!). It only works with certain types of dyes and only on wool and silk. The results are less washfast than on mordanted fibers but it’s still very intriguing, because it doesn’t require metals but is lightfast! I haven’t tried it yet but I want to run some tests this summer and I’ll make sure to report back.

To round it up, above the tests from 5 years back I mentioned before. From left to right of each set: goldenrod, onion skins, heather, avocado, logwood. Colors don’t show too well on camera, so take my word for it - each process seemed to work better for some dyes than the others.

One thing that had the biggest impact on the result was scouring (never skip scouring!) because in the milling process there are often additional substances introduced to the fibers, that later prevent the dyes from attaching. Aluminium obviously made the colors visibly stronger and more vibrant—notice that yellow—but even soy milk worked beautifully with some of the dyes. Tannins seem to not always be the right solution, even if they have potential with particular dyes. And the thread that connects them all—avocado. Just a wonderfully rich dye if extracted properly, it came out great on all the tests, even unscoured cotton took up this pink rather well. So let’s all dye our T-shirts with avocado and not over-complicate it when we don’t have to!

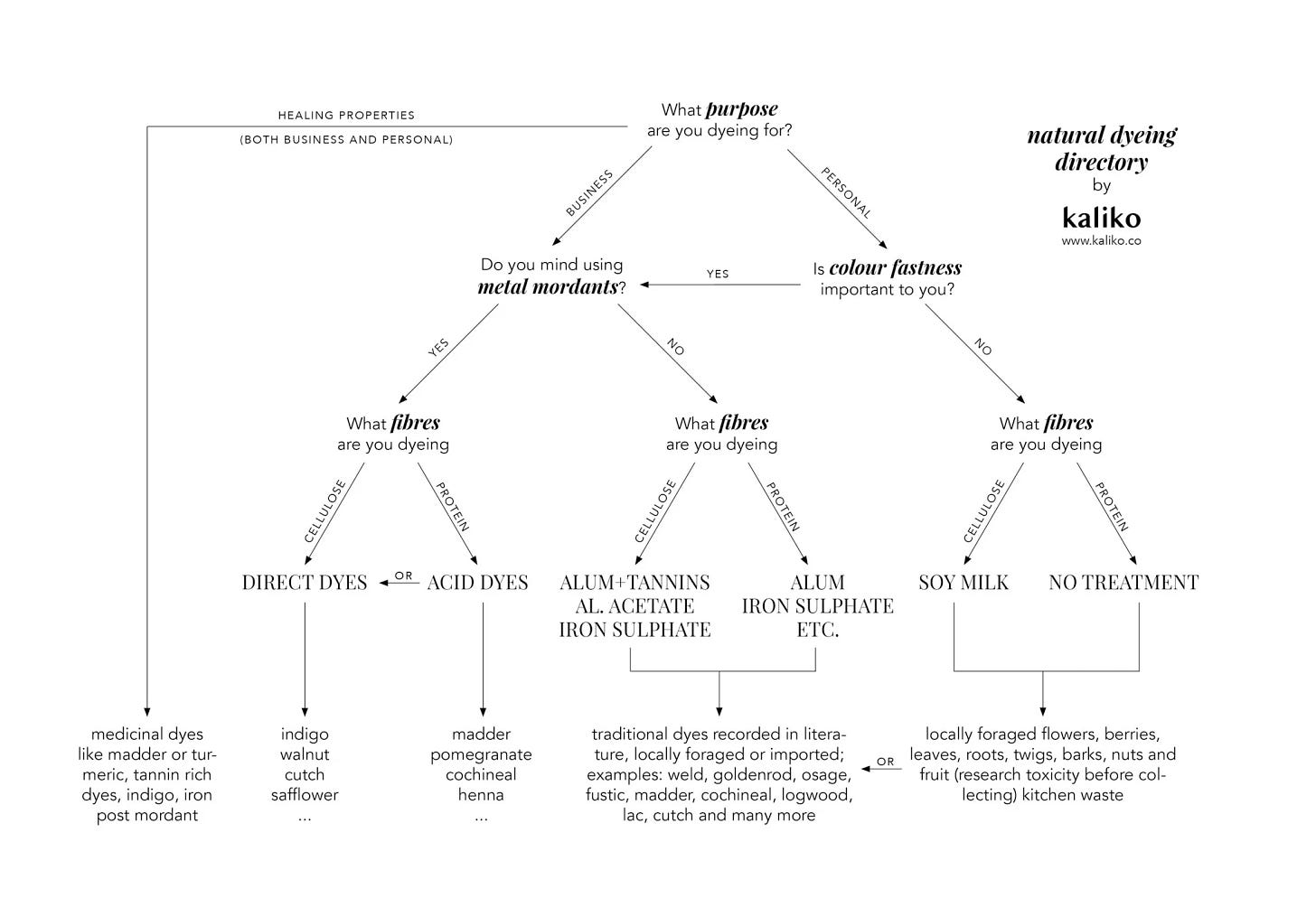

I will leave you with a flowchart I made for my Mordants for natural dyes ebook. Feel free to use it and share it if you find it helpful. (More info on the chart here.)

What process is your go-to?

I’m currently all about vibrant colors, being particularly obsessed with yellow, so there’s no way around aluminium at the moment.

Quick announcement before I go: I’m taking part in Wedding Wool Week in Berlin in July and I’d love to see you there! You can visit my stall on July 14th and 15th or join a Bundle Dyeing Workshop I’m teaching on July 13th.

J'en apprend beaucoup de tes conseils et astuces, wow le lait de soja.belle decouverte, merci